Libretto adapted by John Adams, Elkhanah Pulitzer and Lucia Scheckner from Shakespeare, Plutarch, Virgil and Dryden. Music by John Adams.

“Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale her infinite variety” — William Shakespeare (1564–1616), describing Cleopatra in Antony & Cleopatra”

Cleopatra VII (69BCE–30BCE) devoted her life to learning and experimentation; her scholastic interests included science, philosophy, math and linguistics. With an insatiable curiosity that was supported by ample resources in every respect, she became very ambitious, which was of course perceived as a threat by those concerned about her influence and the power she possessed, or could gain, through political means.

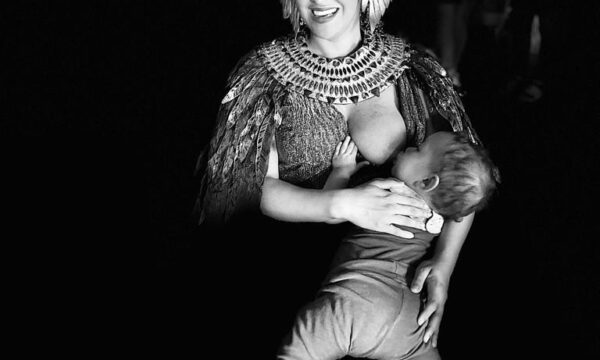

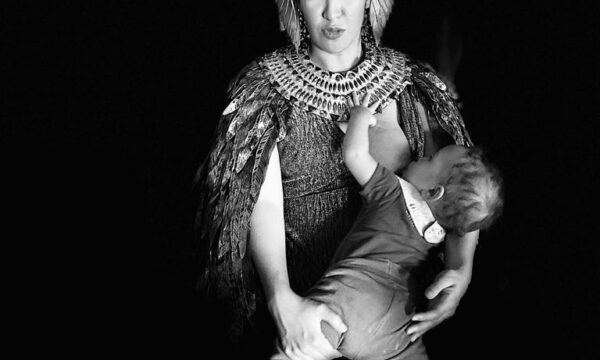

Cleopatra VII’s closest confidants and government advisors were two women, Charmian and Iras. She was the mother of four children, carrying first one child, then a set of twins — whom she named Helios and Selene (Sun and Moon) — and then another baby.

She grew up in a Ptolemaic society where the enactment of violence was an irrefutable and, sadly, commonplace reality (as it was in Roman culture). However, she was also raised in a society where expressing one’s sexuality and personal desires was openly celebrated, never constrained.

Cleopatra VII may have been calculating, as one would expect a political leader to be, but the numerous accounts that project her as merely a hyper-sexed manipulator are based in misogyny – it’s as basic, and complex, as that. (To root this in critical history: one main account of Cleopatra, penned by Plutarch, glorified the rise of the Roman Empire and depicted the demise of Antony and Cleopatra, for the consumption of the Roman people and the all-male senate. This commission was amidst the propaganda and tyranny of Octavian, the Roman emperor who conquered the Ptolemaic kingdom of Egypt. Octavian is referred to as “Caesar” in both the Shakespeare play and the opera, as he renamed himself August Caesar after Julius Caesar. One of the last leaders of the Roman Republic, Julius Caesar was Cleopatra’s first love, and father to her first child, Caesarion.)

Thankfully, I find John Adams’s music and realization of Shakespeare’s text also to be complex. Through the depth of sonic language in this new opera, which may be better characterized as a “sung drama,” Antony & Cleopatra provides just enough space to depict Cleopatra’s ever-expansive personhood and qualities. The material (like so many of John’s operas) is ever-shifting and mercurial, but the piece has a restless, unrelenting sense of uneasiness that permeates the score, and I think it’s because of the extreme uncertainty that Cleopatra, like everyone around her, faced at this time. There’s a pulsating drive that reflects the ways each character is propelled towards their ultimate apex or collapse.

Cleopatra’s connection to Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony) is also intensely captured in this sung drama. Their fervid, fun, ferocious, committed love was personal and political, and they aimed to develop a world that demonstrated their inquisitive and acquisitive mindsets. For a queen who was reputedly capable of anticipating scenarios and almost instantaneously reading people, the only person who seemed to surprise Cleopatra was… her Antony. Maybe that’s what drew her to him, and evidently what led to their shared demise.

One aspect of Cleopatra’s character that has fascinated me, and which is highlighted over and over again throughout this sung drama, is her obsession with security: security for her children, her people, and her person seemed to be a core preoccupation for this Egyptian leader.

She would not tolerate her sense of security to be threatened, or a promise of security to be betrayed. On those occasions when it was, Cleopatra felt compelled to use whatever means necessary to ensure that safety was restored.

At a critical time, when there were no longer any guarantees for herself, her legacy, or her country, she seemed to do the only thing left in her power, and attempted to secure some protection for her children. (I think that’s ultimately why she ended her life on her own terms.)

Although she birthed four children in all, Cleopatra was ultimately survived only by the three fathered by Mark Antony, for her eldest son was tracked down and executed soon after her death. Despite her wish to be remembered as Egyptian, and her embrace of all parts of that identity, her children were raised in a Roman household and it’s unclear how much Egyptian culture was incorporated into their education. (One of her children was named Cleopatra, and went on to be a successful leader.)

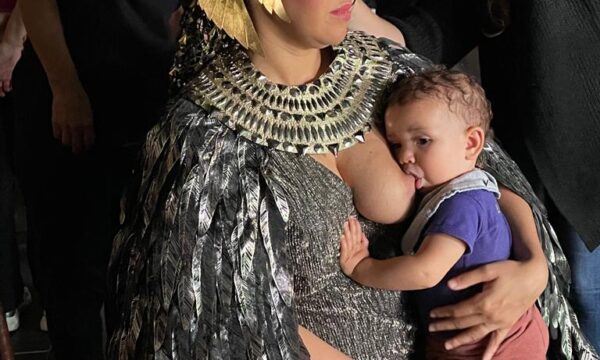

My perspective on Cleopatra is influenced by the realities of my current life as a parent. I relate to her fearlessness, because that quality has grown in me over this past year, in ways that are quiet and clarifying. So, what better lens through which to consider and honor the vast scope, bold presence and eternal influence of the African Queen: an astute, sensual human being who thrived in pursuits of all learning, didn’t deny herself pleasure, was vulnerably devoted to all she loved; and unafraid of sacrifice?